“Short fiction is closer to poetry than to the novel, and very short fiction is even closer.”

James Wood, The New Yorker, March 11, 2013

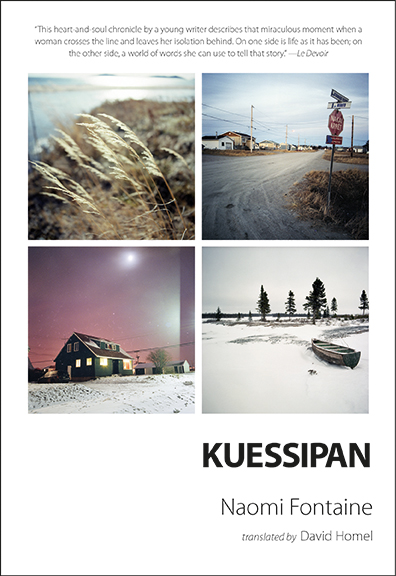

Reviews of this book – I hesitate to call it a novel – tend to focus on author Naomi Fontaine’s life. At 22 she has a child of three and is studying at Université Laval in Quebec City. She was born in the village of Uashat, but left the reserve for a new life in the province’s capital at age seven.

Perhaps this focus on real life is because there is no plot to speak of. Perhaps it is because events have clearly shaped this first-time author’s way of looking at the place where she grew up, of sizing up the suffering behind the poverty, of sharing it with her readers. She does this in a way that is resolutely poetic, that lends a great deal of light and beauty to familiar yet distressing themes of alcoholism, teen pregnancy, abortion, and lives otherwise washed up by the bay on an Innu reserve.

Throughout, the writing is both incredibly simple and effectively poetic, illustrating James Wood’s observation above that, in fiction, brevity takes us closer to poetry.

Each paragraph is a snapshot of everyday life on the reserve, a description of a photo or a memory in the narrator’s mind’s eye, the writing “soft as a partridge’s belly.”

After reading Kuessipan, I felt as though I had just come out on the other side of a collection of poems or had a quick flick through an old photo album. I enjoyed it, without really being able to pinpoint why, just being able to cling to an image or two, a turn of phrase, that left their mark.

Time is meaningless, for example, “like a truck forgotten in a parking lot.” And the Innu language is “harsh, all bark and antlers.”

The result is a beautiful book. Beautiful language, beautifully translated. ≈

IN TRANSLATION

From Kuessipan

by Naomi Fontaine

≈ translated by David Homel (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2013)

Time was meaningless, like a truck forgotten in a parking lot, like a dandelion you thought was a rose – a child’s existence. Sometimes there was nothing for lunch. You climbed onto a chair, took down the biggest bowl you could reach, and served yourself a generous helping of brightly coloured cereal. It tasted good. Then you went back to your friends, who were there where you’d left them by the schoolyard. There weren’t as many as before. They were all waiting for the bell, even the ones who hadn’t gone back to their houses.

At first, you were too young for the parties that went on forever. No more than twelve the first time you blacked out: a silly smile and your cap on backwards. Your eyes had narrowed down to two dots. There was no pain there. No more, any more. Then it came into your life, the thing that seemed too small to be deadly. Get your hands on it, crush it, inhale it. Then be strong. It was all over the reserve, in the houses, on the street. They sold it in small doses, one pill at a time, almost cheap. It was a drug for the poor. The nights went on for weeks. There were no limits. There never had been.

One night, you felt an unspeakable pain between your ribs, then in your guts, like a metal bar piercing your body. You went to the hospital for tests. They found the problem quickly enough: it was your liver. Completely destroyed. You had abused it and it became intolerant. You had to stop using immediately, right now. You were twenty years old.

You went to the city for treatment. You left your village, your poverty, your self-destruction, your friends and family. You started anew somewhere else, and gave it your best shot. You took care of yourself to survive. You were a survivor of your own body. You had to do it. At the end of that filthy journey, you still had hope. So you left.

Like all the other boys, you dreamed of being a fireman, building a house, falling in love. You were little, sitting on the bottom step of the stairs, and you spotted a new car moving slowly up the street. You were going to drive the same kind later on. It would be black, a luxury model, with a girl too pretty for you at your side. You were going to be someone important, a band councillor or a rich worker. You didn’t dream of being the best. You just wanted to be among the better ones.

Did anyone ever tell you that you’re beautiful? ≈